As a golfer, it’s not every day you get to play an uber private and legendary course but years back my husband got to do just that at Royal Troon in Scotland. It was a once-in-a-lifetime round and one courtesy of our dear friends Mary and Brian who we’ve known for many years and who are originally from Scotland. They contacted a dear friend of theirs “back home” who was a member at Troon and before we knew it, he was playing, I was touring, and later we were both inside the clubhouse and locker room with the most hospitable and friendly of Scottish couples and where hubby had to borrow a jacket from the club to wear over his golf shirt in the strict “jackets only” restaurant. We will never forget it and are reminded of it this week as the 152nd British Open is played at Royal Troon’s Old Course.

Founded in 1878, the famous course was designed in the traditional out-and-back manner of another Old Course, St. Andrews. Troon is a tough test and includes a gentle opening through some of the most striking links land found at any Open venue. It wraps things up with a back nine that’s considered as tough as any finish in the world.

As memorable as Troon and all of Scotland was, one of the most unforgettable things we did and that I’ve ever done on any trip is seeing the famous Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo. This pageantry of all pageantry consists of 1,000 musicians, pipers, drummers, singers, and dancers as well as stirring performances of the Massed Pipes and Drums and the Massed Military Bands emerging from the huge castle gates and playing the inspiring battle tunes of Scotland’s famed regiments all with the backdrop of the floodlit Edinburgh Castle. Dramatic, amazing, and mind-blowing don’t even begin to describe it.

As memorable as Troon and all of Scotland was, one of the most unforgettable things we did and that I’ve ever done on any trip is seeing the famous Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo. This pageantry of all pageantry consists of 1,000 musicians, pipers, drummers, singers, and dancers as well as stirring performances of the Massed Pipes and Drums and the Massed Military Bands emerging from the huge castle gates and playing the inspiring battle tunes of Scotland’s famed regiments all with the backdrop of the floodlit Edinburgh Castle. Dramatic, amazing, and mind-blowing don’t even begin to describe it.

If you know anything about golf, you know it originated in Scotland and if you know anything about Scotland, you know it’s also the home of bagpipes. Kind of.

Yes, bagpipes today are officially associated with Scotland, but ancient and medieval art and sculpture dating from 1000 BC depict forerunners of the bagpipe in Middle Eastern, Egyptian, Roman, and Grecian cultures. The earliest appearance in the British Isles didn’t appear until sometime in the 14th century and in his classic “The Canterbury Tales” from 1380, Chaucer mentions “a baggepype wel coude he blowe and sowne.” So, there’s a snippet of its history, but what exactly is a bagpipe?

Yes, bagpipes today are officially associated with Scotland, but ancient and medieval art and sculpture dating from 1000 BC depict forerunners of the bagpipe in Middle Eastern, Egyptian, Roman, and Grecian cultures. The earliest appearance in the British Isles didn’t appear until sometime in the 14th century and in his classic “The Canterbury Tales” from 1380, Chaucer mentions “a baggepype wel coude he blowe and sowne.” So, there’s a snippet of its history, but what exactly is a bagpipe?

There remain several versions of the bagpipe, but the one we are most familiar with is the Scottish Highland one consisting of three drone pipes on the top of the bag and a nine-note chanter pipe along with a bag made out of sheep or elk skin.

There remain several versions of the bagpipe, but the one we are most familiar with is the Scottish Highland one consisting of three drone pipes on the top of the bag and a nine-note chanter pipe along with a bag made out of sheep or elk skin.

From the bagpipe’s first days in Scotland, tradition had it that each town had an official tax-funded bagpiper who played at formal occasions, country fairs, weddings, and in churches. Not only were pipes entertaining, they were also protective. The first mention of bagpipes used as instruments to spur on the troops occurred at the Battle of Pinkie in 1549 and in 1746, they were used in the Scots’ failed Battle of Culloden, after which the instrument was banned by the British for 40 years.

But, by WWI, the Brits had adopted 2,500 Scottish comrades to bravely lead the troops into battle, many of whom were killed or wounded by the Germans. Pipers were then forbidden on WWII front lines but one brave Scottish piper called Private “Mad” Bill Millin could be heard on D-Day through gunfire on Normandy Beach.

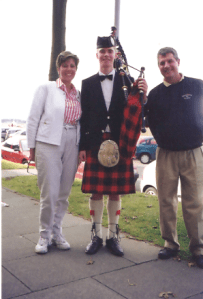

As important as the pipe itself is, so is what a piper wears, often called the “full highland dress No. 1.” Essentials are traditionally the tall, ostrich feather bonnet; a highly decorated jacket and plaid kilt; a short sword called a dirk at the side; a large bejeweled brooch; horsehair tassels called sporran; and white spats, short for spatterdashes or spatter guards, which cover the instep and the ankle. As for what’s worn under a kilt; well, that’s a tale all its own.

As important as the pipe itself is, so is what a piper wears, often called the “full highland dress No. 1.” Essentials are traditionally the tall, ostrich feather bonnet; a highly decorated jacket and plaid kilt; a short sword called a dirk at the side; a large bejeweled brooch; horsehair tassels called sporran; and white spats, short for spatterdashes or spatter guards, which cover the instep and the ankle. As for what’s worn under a kilt; well, that’s a tale all its own.

Most of us have heard that it’s a Scottish tradition to not wear undies under a kilt. If you ask a kilt-wearing gent that question, you might regret doing so as his answer could vary and very well embarrass you, not him. (I may or may not have asked the piper pictured above with me and hubby!) Historically, many believe the tradition of not wearing undergarments under a kilt began in Scottish military regiments. It is rumored that the Scottish military code from the 18th century prescribed a kilt but did not mention underwear so Scottish soldiers took that as a challenge rather than an oversight and the underwear-less tradition began. The popular saying “going commando” evolved from this and the rest is kilt and underwear history. Oddly enough, Scottish regiments wore kilts in combat until they were banned during WWII for fear that a Scotsmen’s private parts would be exposed to chemical weapons. Ouchie! Some still consider it inauthentic to wear underwear while others insist that the regimental style is outdated and unhygienic. Today, a Scot’s choice of commando or not is theirs and theirs alone but I did learn that The Scottish Official Board of Highland Dancing has made underwear part of the dress code. Apparently, one’s approach to what they wear under their kilt is as varied as the kilt tartans themselves. So really quickly; what is a tartan?

Most of us have heard that it’s a Scottish tradition to not wear undies under a kilt. If you ask a kilt-wearing gent that question, you might regret doing so as his answer could vary and very well embarrass you, not him. (I may or may not have asked the piper pictured above with me and hubby!) Historically, many believe the tradition of not wearing undergarments under a kilt began in Scottish military regiments. It is rumored that the Scottish military code from the 18th century prescribed a kilt but did not mention underwear so Scottish soldiers took that as a challenge rather than an oversight and the underwear-less tradition began. The popular saying “going commando” evolved from this and the rest is kilt and underwear history. Oddly enough, Scottish regiments wore kilts in combat until they were banned during WWII for fear that a Scotsmen’s private parts would be exposed to chemical weapons. Ouchie! Some still consider it inauthentic to wear underwear while others insist that the regimental style is outdated and unhygienic. Today, a Scot’s choice of commando or not is theirs and theirs alone but I did learn that The Scottish Official Board of Highland Dancing has made underwear part of the dress code. Apparently, one’s approach to what they wear under their kilt is as varied as the kilt tartans themselves. So really quickly; what is a tartan?

We are all guilty of using the term “plaid” when talking about any fabric that has checks going this way and that. But a plaid is actually a long piece of wool worn over the shoulder as part of traditional Highland dress. Tartan, on the other hand, is a checked pattern that has stripes meeting at a 90-degree angle and the vertical stripes are exact duplicates of the horizontal ones. A tartan is a weave of colored threads registered with the Scottish Tartan Authority and owned by specific families and clans. For true traditionalists and those in Scotland, tartan is a pattern while plaid is a piece of cloth that consists of tartan prints.

We are all guilty of using the term “plaid” when talking about any fabric that has checks going this way and that. But a plaid is actually a long piece of wool worn over the shoulder as part of traditional Highland dress. Tartan, on the other hand, is a checked pattern that has stripes meeting at a 90-degree angle and the vertical stripes are exact duplicates of the horizontal ones. A tartan is a weave of colored threads registered with the Scottish Tartan Authority and owned by specific families and clans. For true traditionalists and those in Scotland, tartan is a pattern while plaid is a piece of cloth that consists of tartan prints.

One of the most famous plaids is the iconic Burberry plaid. Established in London in 1856 by Thomas Burberry, the brand’s distinctive plaid is recognized and imitated the world over. The Burberry plaid is a tartan recognized by the Scottish Tartan Authority and forever a fave of mine.

But back to bagpipes.

I love a good bagpipe. I loved them in Scotland and I love them at parades, weddings, and even funerals. There is something so unique about them and their sound and when accompanied by snare, tenor, and bass drums in a “pipe band,” there is nothing comparable.

I love a good bagpipe. I loved them in Scotland and I love them at parades, weddings, and even funerals. There is something so unique about them and their sound and when accompanied by snare, tenor, and bass drums in a “pipe band,” there is nothing comparable.

Considered a woodwind instrument using enclosed reeds fed from a constant reservoir of air in the form of a bag, bagpipes are equally complex and simple. The most common “Scottish Highland” bagpipes consist of a few pipes all connected to the bag, with the main melody pipe, called the “chanter,” in the same family as a double-reed oboe and bassoon. The other pipes are often single reed like clarinets and saxophones.

The chanter pipe plays the melody and is pitched in a certain scale by covering holes, like a recorder or song flute, while the continuous tone of the “drone” pipes is each pitched on one note. Close your eyes and you can probably hear that distinctive drone sound as a bagpipe warms up. But what about the bag?

That floppy bag, traditionally made from skins, actually serves as a “third lung” to store air. Interestingly enough, a piper doesn’t blow directly into the pipes but into the bag. He then uses arm pressure to squeeze air out of the bag and into the pipes. His goal is to keep refilling the bag with air so it never runs out, which results in an unbroken and continuous tone.

That floppy bag, traditionally made from skins, actually serves as a “third lung” to store air. Interestingly enough, a piper doesn’t blow directly into the pipes but into the bag. He then uses arm pressure to squeeze air out of the bag and into the pipes. His goal is to keep refilling the bag with air so it never runs out, which results in an unbroken and continuous tone.

Bagpipes and all things related to them are not only interesting but historical. They look pretty and they sound pretty and they make for a pretty good story.

If I’ve piqued your interest in bagpipes and if you’re going to be in New York City, you might want to check out the extensive collection of historical bagpipes at the Metropolitan Museum of Art or check out the work of American composer Michael Kurek, whose compositions I learned a lot from. Better yet: go to Scotland! You might even want to buy yourself a kilt!

If I’ve piqued your interest in bagpipes and if you’re going to be in New York City, you might want to check out the extensive collection of historical bagpipes at the Metropolitan Museum of Art or check out the work of American composer Michael Kurek, whose compositions I learned a lot from. Better yet: go to Scotland! You might even want to buy yourself a kilt!